Tuesday, July 31, 2012

Shades of Purple, Shades of Perfection

Something about this pairing struck me.

Complementary coloration, perhaps. The aubergine foliage of Happy Single Flame Dahlia, juxtaposed to the overt magentic tones of the lily illustrate just how vast is the spectrum of the color purple.

Or is it competition?

Or might it be the struggle for perfection: which of the two has won this elusive quest?

Some amongst us are obsessed with perfection. Yes, there are aesthetes who find and are deeply satisfied by the presence of beauty in art and nature. They find perfection in the stroke of a brush, or the petal of a flower.

But can these things be perfect? Whatever is meant by perfection in the case of a landscape or a painting?

Aristotle long ago (in Book Delta of Metaphysics) mused on perfection, and defined it as:

(a) that which is complete,

(b) that which is so good that nothing could be better, or,

(c) that which has attained its purpose.

But what is complete? If we refer to mortal things, then no mortal could logically be perfect in this first sense of the term until we die: for only then is our life complete. Perfection, then, is a judgment or assessment made by others. But by completeness, Aristotle meant that which contains all requisite parts, or, put differently, to that which is whole or undivided. On that view, we mortal beings are complete in a biological sense, but in a social sense we are not complete or perfect as automatons: we are, as Aristotle noted in The Politics, social animals, political ones even, who become complete by living amongst and with, in community if not always in communion with others. And so, we are perfect in this specific sense.

But what has attained its purpose? Is a flower perfect only after it has given its pollen to the bee or to the wind so that it may be reproduced? Or is a flower perfect only by virtue of being itself? The aesthete would favor the latter position, of course. For us mortal beings, perfection in this teleological sense is, as with the first sense, seemingly a judgment made by others--one made properly after we have passed. Yet that is but one side of the proverbial coin, no? Here, Aristotle might have answered the question in his Ethics (gosh, human beings were so productive before the age of the television, the Wii, and sundry other electronic sources of entertainment).

Eudaimonia--commonly translated as happiness, but more appropriately construed as human welfare or human flourishing--is the highest good for humans, even if the specific content of our flourishing or living well is disputed. But is a "good" the same thing as "purpose" or "end" or telos? Technically no, but an argument can be made that defining what flourishing and living well means for us as individuals is our telos, our purpose. We each discover what this means--and in our various modes of individual flourishing, we contribute to human flourishing. And so we become perfect in this sense.

But what of perfection in the second sense? Innocuously, it might instigate us to hyperbole: "This is the most beautiful or perfect flower or landscape or vista," or "this dinner is perfect." How many of us have done that? This might be the aesthete's cold or virus.

More dangerously, though, this conception of perfection is the most problematic, for defining it as that which is so good that nothing could be better is the cell that introduces the malignant disease of perfectionism. And each of us knows perfectionists: those possessive of, and possessed by, an insatiable need to create that which is beyond reproach, or who berates the self for not being X enough (X may be variously defined as skinny, beautiful, smart, sexy, kind, caring, worthy, creative, happy, optimistic, and sundry other judgments).

We berate ourselves for our too lumpy mashed potatoes, or the smudge on our painting, or the dried leaves on our prized plant before visitors are about to descend on one's garden. We can't write because we deem our prose not eloquent enough. We proclaim ourselves stupid. Perfectionism is healthy in small doses, but a fetid sore when we exceed our daily recommended dosage.

Perfectionism, it seems to me, is the antithesis of perfection, for it might be yet another example of an ideology. Ideologies, Hannah Arendt wrote, are "isms which to the satisfaction of their adherents can explain everything and every occurrence by deducing it from a single premise." To modify this a bit, perfectionists can explain every failing by measuring it against a single, idealized image or premise. We think we are Chopin, yet our piano playing can never quite match Chopin's. Well, I ask: "why the hell should it? Are you Chopin? No. He died a long time ago."

We are who we are, and that is perhaps the most difficult and challenging realization many of us must make during our lives. We are not Martha Stewart, try as I might (er, confession anyone?), nor are we Chopin. We are not the hottie gymnast (uh, pluralize that) on the US men's gymnastics Olympic team--so no, our body doesn't look that great (perhaps it would if we devoted 3/4 of our waking days to training), and no, we can't sleep with them (damn subconscious!). We are who we are.

Sure, we will fail at things and screw up at others. But we will excel in others--and even that in which we excel will sometimes challenge us. Only through challenges will we flourish.

Perfection, like purple, comes in so many shades. The point is to realize it.

Monday, July 30, 2012

"The Rose of Sharon"

I had always thought that the Rose of Sharon was a type of Hibiscus (Hibiscus syriacus, to be exact). A visit to most garden centers will confirm this, though the hibiscus in question eponymously, and quite erroneously, attributes its origins to Syria when in fact it hails from East Asia (and is in fact the national flower of South Korea).

But Rose of Sharon, I have learned, also refers to Hypericum calycinum, better known as St. John's Wort, which of course bears no resemblance or filial relation to the hibiscus.

So we have two different plants with the same common name. Curious, isn't it?

Sort of, but not really, because Rose of Sharon also has come to be attached to a crocus (this is confirmed as a mistranslation of the Hebrew כרכום, karkōm, which grew on the plains of Sharon along the Mediterranean Sea in what is today northern Israel). Confusion may have stemmed from the fact that the crocus bears some resemblance to a previously unidentified, onion-like flowering bulb, Chavatzelet HaSharon, חבצלת השרון, which has been authoritatively identified as Pancratium maritimum, a.k.a. Sand Lily or Sand Daffodil, pictured below.

And the name has been attached to a type of tulip.

And to a type of lily.

Confusion is nothing new.

This is why I try to learn the formal botanical (Latin) names for plants: because their common names mislead.

But then so too do the Latin names, as knowledge becomes more precise, and as knowledge is created.

I do not have the Rose of Sharon, but I do have Rose Mallow in my garden. I've written about her several times; she is a stunning addition to any garden, and responds well to being accorded a place of prominence where she is permitted to be the belle of the ball.

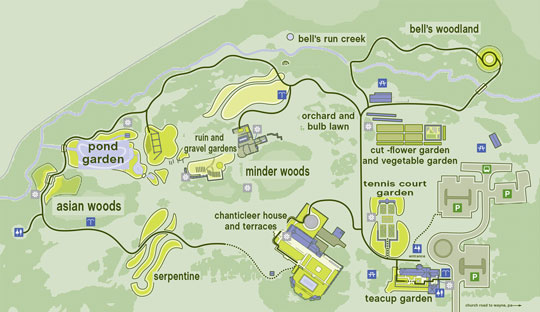

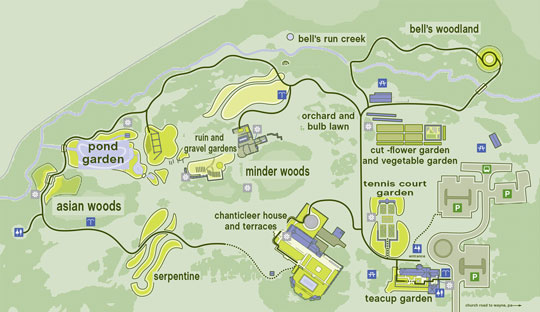

I do not have the Rose of Sharon, but I do have Rose Mallow in my garden. I've written about her several times; she is a stunning addition to any garden, and responds well to being accorded a place of prominence where she is permitted to be the belle of the ball.(For comparison: I spied a Rose Mallow in the Chanticleer Pond Garden [toward the upper left of the photograph], but it rather gets lost. This is not a point of criticism, for Chanticleer is designed as an Impressionistic tapestry, each plant prominent only for its placement in and contribution to a wider order, a punctuation of color and texture; in the small garden, plants must be selected that both contribute to a wider order and that stand alone as exemplars of a moment or a vision.)

My friend and neighbor, Sharon, loved my Rose Mallow. In fact, she wanted it after we began her garden.

For a moment, I choked. How could I tell her that while Rose Mallow is surprisingly unfussy, she is the botanical equivalent of a bibber, our summer drinks on the porch notwithstanding? And my Sharon made it quite clear she needed low maintenance plants because she had a self-professed "black thumb."

I responded that I'd be happy to divide her once she became acclimated, but that she needed copious amounts of water.

And out came classic Sharon: "Girrrrlllllll.....you'd best keep her over there so I can look at her pretty! You be bothered, but I can't be. Just as well: I can look out at her everyday, so keep her growing. I get all the pretty and you all the work!"

And out came classic Sharon: "Girrrrlllllll.....you'd best keep her over there so I can look at her pretty! You be bothered, but I can't be. Just as well: I can look out at her everyday, so keep her growing. I get all the pretty and you all the work!"And we laughed.

Last year, Rose Mallow reached approximately 12 feet with five stalks. This year, she sports seven stalks, at approximately the same height. And oh, the flowers she produces!

Our Sharon, our beautiful Sharon, took her leave late yesterday from this earthly existence. She...died. (Take note: how powerful are our words, but more so the tenses of our verbs.) She took her enormous heart, and her infinite goodness, out into other worlds.

And so my Rose Mallow becomes my inadvertent Rose of Sharon. Perhaps this is how these common names come to refer to a wide variety of plants: our proclivities and personal experiences, our understandings and our misunderstandings, shape our perceptions and we locate, create, linkages between otherwise disparate items. These common names create order where there was none, provide comfort and assurance in a world of uncertainty and confusion.

And so my Rose Mallow becomes my inadvertent Rose of Sharon. Perhaps this is how these common names come to refer to a wide variety of plants: our proclivities and personal experiences, our understandings and our misunderstandings, shape our perceptions and we locate, create, linkages between otherwise disparate items. These common names create order where there was none, provide comfort and assurance in a world of uncertainty and confusion.Genesis: the beginning. A beginning. Naming: Adam's contribution to that beginning. And where there are no names, or when names are altered at will for self-benefit, or when names lose their meaning...well, we need only think of Thucydides' account of the stasis at Corcyra to understand the peril the befalls us.

We all felt bereft last night, huddled together, remembering and laughing and sharing stories: our mortal way to grasp onto ethereal meaning. We have to reiterate names, name names, ascribe meaning and importance to them all over again...lest we lose them too. That is what we humans do: we attempt to regularize and stabilize; some might call this an exercise of proprietorship, but that misses the mark. We are all mortal in an immortal world. We seek a continuity otherwise lost to us ephemeral beings.

We all felt bereft last night, huddled together, remembering and laughing and sharing stories: our mortal way to grasp onto ethereal meaning. We have to reiterate names, name names, ascribe meaning and importance to them all over again...lest we lose them too. That is what we humans do: we attempt to regularize and stabilize; some might call this an exercise of proprietorship, but that misses the mark. We are all mortal in an immortal world. We seek a continuity otherwise lost to us ephemeral beings.For me, Sharon--the woman, the name--will always be synonymous with strength and fortitude, not just of physicality, but of character and spirit. She did not tolerate intolerance or bigotry, rudeness or shenanigans. She rose above the fray and taught all of us, in her no-nonsense, genuine, and always sassy kind of way, how to be human.

She was a beacon of light, just as Rose Mallow is a mid- to late-summer floral beacon on our block.

Now, Rose Mallow stands alone, bereft of that other rose in our lives.

Rose Mallow extends into the sky, stretching forth, always there, a beacon, to guide the spirit of Sharon back to the place of her earthly life.

** In memory of our beloved Sharon Thompson **

Wednesday, July 25, 2012

Other People's Gardens: Chanticleer's Ruins

Viet loves all things skull and crossbones.

Socks, belts, bags, tie-clips, and ties: these evidence his fascination for a symbol from which many people shirk.

So when Lauren and I happened upon the Ruin Garden at Chanticleer, and in particular one feature of the garden, I whispered to myself, "Viet would love this."

Adolf Rosengarten, Jr., lived in Minder House, built in 1925, on the Chanticleer estate just down the hill from his parents' mansion. In 1999, an idea possessed him: every great garden estate needs a ruin.

And so he razed his house and constructed a ruin on Minder House's foundations. The things rich people do...

The effect, while a bit kitschy, can be visually dramatic.

A giant sarcophagus-fountain greets the visitor upon entering the ruined house, flanked at one end by a fireplace that withstood the calamity that the visitor is supposed to think brought down a great house.

Schist walls hemorrhage plants.

Trees emerge from deserted floors, yearning to be free, like the banyans growing up and out from the famed Khmer temple, Angkor Wat.

Nature reclaims her territory. She must.

In the "library," books litter the floor. Titles satisfy the visitor's thirst for kitsch.

And a fire of ferns beckons the visitor to sit and read for a while.

But one section of the great house, the "Pool Room," captured my imagination, only because Viet would delight.

At first, the "billiard" table doesn't look like much, having been transformed into a fountain.

But on closer inspection, one finds the ghosts of inhabitants past gazing up past the visitor towards an image of a home in which they once resided.

And I thought, "Death be not proud."

Socks, belts, bags, tie-clips, and ties: these evidence his fascination for a symbol from which many people shirk.

So when Lauren and I happened upon the Ruin Garden at Chanticleer, and in particular one feature of the garden, I whispered to myself, "Viet would love this."

Adolf Rosengarten, Jr., lived in Minder House, built in 1925, on the Chanticleer estate just down the hill from his parents' mansion. In 1999, an idea possessed him: every great garden estate needs a ruin.

And so he razed his house and constructed a ruin on Minder House's foundations. The things rich people do...

The effect, while a bit kitschy, can be visually dramatic.

A giant sarcophagus-fountain greets the visitor upon entering the ruined house, flanked at one end by a fireplace that withstood the calamity that the visitor is supposed to think brought down a great house.

Schist walls hemorrhage plants.

Trees emerge from deserted floors, yearning to be free, like the banyans growing up and out from the famed Khmer temple, Angkor Wat.

Nature reclaims her territory. She must.

In the "library," books litter the floor. Titles satisfy the visitor's thirst for kitsch.

And a fire of ferns beckons the visitor to sit and read for a while.

But one section of the great house, the "Pool Room," captured my imagination, only because Viet would delight.

At first, the "billiard" table doesn't look like much, having been transformed into a fountain.

But on closer inspection, one finds the ghosts of inhabitants past gazing up past the visitor towards an image of a home in which they once resided.

And I thought, "Death be not proud."

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think'st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be,

Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee do go,

Rest of their bones, and soul's delivery.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke; why swell'st thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally,

And death shall be no more, death, thou shalt die.

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think'st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be,

Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee do go,

Rest of their bones, and soul's delivery.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke; why swell'st thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally,

And death shall be no more, death, thou shalt die.

--John Donne, the 10th sonnet of his Holy Sonnets

Other People's Gardens: Chanticleer's Teacup Garden

I hereby declare GIN to be the official GARDENER'S beverage. Not ice tea or lemonade, not the necessary glass of water. No.

Gin.

Why?

Well, it owes to the obvious: I garden. I like gin. No, I love gin. 'Nuff said.

Well, it owes to the obvious: I garden. I like gin. No, I love gin. 'Nuff said.

Seriously, though, any drink made with so many botanicals (the juniper berry joined by diverse and various combinations of almond, anise, bitter orange, cassia bark, cinnamon, coriander, cubeb, cucumber, frankincense, grains of paradise [a.k.a. Guinea pepper], lemon, licorice root, lime peel, nutmeg, orris root, rose petals, saffron, and savory) must be a friend to the gardener.

It's no secret that I thoroughly enjoy a gin and tonic. I especially LOVE Edinburgh Gin (to which Viet introduced and treated me last year with a bottle direct from Edinburgh as a birthday gift), because of its triumvirate of powerful flavors. When the gin first hits the palate, the milkiness of the Scottish Thistle titillates, and prepares the tastebuds for a mass eruption of the florals of the Scottish Heather, soon followed, after swallowing, by the spicy sharpness of Scottish Juniper. Apparently, the milk thistle strengthens the liver, helping it to remove toxins from the system. Must be why the Scots added it....so they could drink more.

So on Sunday I experienced the ultimate birthday confluence: gardens and gin and tonic. My friend Lauren treated me, after a scrumptious brunch at the White Dog Cafe in Wayne, PA, to a garden tour of Chanticleer.

No, no, dear reader. The staff at Chanticleer does not serve gin and tonics under the stone portico overlooking a portion of its magnificent gardens. No. Perhaps they should, as Lauren and I sat in those delightful rocking chairs overlooking the valley to the Lotus Pond, feeling the breeze caress our faces...

The connection (aside from the fact I promptly made a G&T as soon as I walked in the door) lies with the Rosengarten & Sons pharmaceutical company, which, founded in 1822 and absorbed by Merck & Co. in 1927, produced quinine (the chief flavoring in tonic). Chanticleer was the country house of the Rosengarten family.

Swoon.

I love this family: gardens, fabulous house, great architecture, stellar gardens, quinine (and by extension, in my warped, gin-soaked mind, Gin and Tonics), antiques, and literary wit.

Yes, about that wit. Adolph Rosengarten, Sr. played upon the fictional Chanticlere of Thackeray's 1855 novel The Newcomes, which was "mortgaged up to the very castle windows," but "still the show of the country," in naming his estate. In French, Chanticleer (chanter, to sing + cler, clear) has come to mean a rooster. Like the Gallic Rooster, Le coq gaulois, the unofficial national symbol of France, one finds understated (and sometimes not so understated), rooster motifs throughout the estate.

[Footnote: The red rooster dominates the flag of Wallonia, the southern French-speaking region of Belgium. It's capital is Namur, and its largest metropolitan area is Liège, and though Viet and I went to both cities in 2010, I can assuredly note that I never saw this flag with its bright red...rooster. That would have been noticeable.

[Footnote: The red rooster dominates the flag of Wallonia, the southern French-speaking region of Belgium. It's capital is Namur, and its largest metropolitan area is Liège, and though Viet and I went to both cities in 2010, I can assuredly note that I never saw this flag with its bright red...rooster. That would have been noticeable.

But what was noticeable: the Walloons persistently genuflected before their wealthier confederal partners, the Dutch-speaking Flemish. For instance, street signs in Wallonia appeared in both French and Dutch; in Flanders, street signs only appeared in Dutch. Walloons apparently need the Flemish more than the Flemish need their poorer southern neighbors. Velvet revolution anyone?]

But I digress.

Chanticleer is spectacular. No wonder why Jacki Lyden of NPR fame recently called it "quite simply, one of the most delightful gardens in the world."

It is: thirty-five acres of sublime plantings.

I especially relish the emphasis on foliar ensemble. This is the crux of my design style; flowers are lovely, but a deeper, more philosophical discussion ensues when attention concentrates on foliage.

For instance, look at this Strobilanthes dyerlanus, with its lovely magenta coloring. By itself, it makes quite a statement, especially as it is accented by the lime green leaves of the unidentified plant to the right.

Yet when one gets up close to that unidentified plant, one seems the magenta veining of the leaves, and those incredibly sharp thorns. This is gardening at its finest.

Those plants were in the Lower Courtyard of the Teacup Garden, our first stop during our visit. The Teacup Garden

reminded me of the White Garden at Sissinghurst, which has at its center a 17th century Chinese oil or ginger jar. The Teacup Garden is used to display ephemerals: all of the tropicals and sub-tropicals that do well in the steamy Pennsylvania summer, but otherwise die when temperatures fall.

Enormous Papyrus are made to shine from below by exquisite pairings of Dusty Miller with the maroon-leafed coleuses, Musa Black Thai,

and, one of my favorites in the garden, Gossypium herbaceum 'Nigra' with its stunning flowers attached to perfectly red stems.

The Teacup Garden is a wonderful introduction to Chanticleer. It must be the melancholic in me (though aren't all gardeners tinged with melancholia, never able to live in the moment, always recalling a past arrangement or imagining a different future?), but while some would revel in the exuberance of tropicals--quite the spectacle as one emerges from the Provence-style small interlude they call the kitchen garden,

which, though distinct and technically a "stop" on the tour, really is but a passage from the front gate to the Teacup Garden--I instead interpreted the garden differently once we dropped down in elevation to the Asian Woods. For the movement was one between stages of life: from the exuberance of youth to the staid maturity of the Asian Woods.

Or one could view the Teacup Garden as a summary of all that lies before the visitor: a view of the ephemerality of life. We are all tropicals awaiting that hard frost that takes us away. But that is just too melancholic...even for me, prone as I am to bouts of lamenting the passage of time.

Or one could view the Teacup Garden as a summary of all that lies before the visitor: a view of the ephemerality of life. We are all tropicals awaiting that hard frost that takes us away. But that is just too melancholic...even for me, prone as I am to bouts of lamenting the passage of time.

Blame it on the birthday--one that indicated I could no longer comfortably lie and say I am 40. We certainly can't blame it on the G&Ts, for those came afterwards.

There is far too much at Chanticleer, far too much seen and experienced, to comment upon in this post. I suppose I'll need to create separate entries.

In the meantime, go to Chanticleer if you are ever in the Philadelphia area. It cannot be missed.

Gin.

Why?

Well, it owes to the obvious: I garden. I like gin. No, I love gin. 'Nuff said.

Well, it owes to the obvious: I garden. I like gin. No, I love gin. 'Nuff said.Seriously, though, any drink made with so many botanicals (the juniper berry joined by diverse and various combinations of almond, anise, bitter orange, cassia bark, cinnamon, coriander, cubeb, cucumber, frankincense, grains of paradise [a.k.a. Guinea pepper], lemon, licorice root, lime peel, nutmeg, orris root, rose petals, saffron, and savory) must be a friend to the gardener.

It's no secret that I thoroughly enjoy a gin and tonic. I especially LOVE Edinburgh Gin (to which Viet introduced and treated me last year with a bottle direct from Edinburgh as a birthday gift), because of its triumvirate of powerful flavors. When the gin first hits the palate, the milkiness of the Scottish Thistle titillates, and prepares the tastebuds for a mass eruption of the florals of the Scottish Heather, soon followed, after swallowing, by the spicy sharpness of Scottish Juniper. Apparently, the milk thistle strengthens the liver, helping it to remove toxins from the system. Must be why the Scots added it....so they could drink more.

So on Sunday I experienced the ultimate birthday confluence: gardens and gin and tonic. My friend Lauren treated me, after a scrumptious brunch at the White Dog Cafe in Wayne, PA, to a garden tour of Chanticleer.

No, no, dear reader. The staff at Chanticleer does not serve gin and tonics under the stone portico overlooking a portion of its magnificent gardens. No. Perhaps they should, as Lauren and I sat in those delightful rocking chairs overlooking the valley to the Lotus Pond, feeling the breeze caress our faces...

The connection (aside from the fact I promptly made a G&T as soon as I walked in the door) lies with the Rosengarten & Sons pharmaceutical company, which, founded in 1822 and absorbed by Merck & Co. in 1927, produced quinine (the chief flavoring in tonic). Chanticleer was the country house of the Rosengarten family.

Swoon.

I love this family: gardens, fabulous house, great architecture, stellar gardens, quinine (and by extension, in my warped, gin-soaked mind, Gin and Tonics), antiques, and literary wit.

Yes, about that wit. Adolph Rosengarten, Sr. played upon the fictional Chanticlere of Thackeray's 1855 novel The Newcomes, which was "mortgaged up to the very castle windows," but "still the show of the country," in naming his estate. In French, Chanticleer (chanter, to sing + cler, clear) has come to mean a rooster. Like the Gallic Rooster, Le coq gaulois, the unofficial national symbol of France, one finds understated (and sometimes not so understated), rooster motifs throughout the estate.

[Footnote: The red rooster dominates the flag of Wallonia, the southern French-speaking region of Belgium. It's capital is Namur, and its largest metropolitan area is Liège, and though Viet and I went to both cities in 2010, I can assuredly note that I never saw this flag with its bright red...rooster. That would have been noticeable.

[Footnote: The red rooster dominates the flag of Wallonia, the southern French-speaking region of Belgium. It's capital is Namur, and its largest metropolitan area is Liège, and though Viet and I went to both cities in 2010, I can assuredly note that I never saw this flag with its bright red...rooster. That would have been noticeable.But what was noticeable: the Walloons persistently genuflected before their wealthier confederal partners, the Dutch-speaking Flemish. For instance, street signs in Wallonia appeared in both French and Dutch; in Flanders, street signs only appeared in Dutch. Walloons apparently need the Flemish more than the Flemish need their poorer southern neighbors. Velvet revolution anyone?]

But I digress.

Chanticleer is spectacular. No wonder why Jacki Lyden of NPR fame recently called it "quite simply, one of the most delightful gardens in the world."

It is: thirty-five acres of sublime plantings.

I especially relish the emphasis on foliar ensemble. This is the crux of my design style; flowers are lovely, but a deeper, more philosophical discussion ensues when attention concentrates on foliage.

For instance, look at this Strobilanthes dyerlanus, with its lovely magenta coloring. By itself, it makes quite a statement, especially as it is accented by the lime green leaves of the unidentified plant to the right.

Yet when one gets up close to that unidentified plant, one seems the magenta veining of the leaves, and those incredibly sharp thorns. This is gardening at its finest.

Those plants were in the Lower Courtyard of the Teacup Garden, our first stop during our visit. The Teacup Garden

reminded me of the White Garden at Sissinghurst, which has at its center a 17th century Chinese oil or ginger jar. The Teacup Garden is used to display ephemerals: all of the tropicals and sub-tropicals that do well in the steamy Pennsylvania summer, but otherwise die when temperatures fall.

Enormous Papyrus are made to shine from below by exquisite pairings of Dusty Miller with the maroon-leafed coleuses, Musa Black Thai,

and, one of my favorites in the garden, Gossypium herbaceum 'Nigra' with its stunning flowers attached to perfectly red stems.

The Teacup Garden is a wonderful introduction to Chanticleer. It must be the melancholic in me (though aren't all gardeners tinged with melancholia, never able to live in the moment, always recalling a past arrangement or imagining a different future?), but while some would revel in the exuberance of tropicals--quite the spectacle as one emerges from the Provence-style small interlude they call the kitchen garden,

which, though distinct and technically a "stop" on the tour, really is but a passage from the front gate to the Teacup Garden--I instead interpreted the garden differently once we dropped down in elevation to the Asian Woods. For the movement was one between stages of life: from the exuberance of youth to the staid maturity of the Asian Woods.

Or one could view the Teacup Garden as a summary of all that lies before the visitor: a view of the ephemerality of life. We are all tropicals awaiting that hard frost that takes us away. But that is just too melancholic...even for me, prone as I am to bouts of lamenting the passage of time.

Or one could view the Teacup Garden as a summary of all that lies before the visitor: a view of the ephemerality of life. We are all tropicals awaiting that hard frost that takes us away. But that is just too melancholic...even for me, prone as I am to bouts of lamenting the passage of time.Blame it on the birthday--one that indicated I could no longer comfortably lie and say I am 40. We certainly can't blame it on the G&Ts, for those came afterwards.

There is far too much at Chanticleer, far too much seen and experienced, to comment upon in this post. I suppose I'll need to create separate entries.

In the meantime, go to Chanticleer if you are ever in the Philadelphia area. It cannot be missed.

Monday, July 16, 2012

Adonidis horti

Viet and I began going to the gym in January 2011 after one of his several many aunts who had not seen us in 5 years called us fat. Yes, I had been aware that tenure and life after 40 trampled down my youthful metabolism, and many a suit pant no longer fit. But her comment proved the straw that broke my camel's back, for she hit with exacting precision the raw nerve that was my weight issue.

The truth of the matter (in the interests of semi-full disclosure) is that I was once, many, many years ago, a self-professed "shadow-itarian:" if it cast a shadow, I wouldn't eat it. I did quickly see the folly of that, and so ate puffed rice, but that was all I ate. I damned myself in many ways. Enough said. My weight issues were an illness...hence the radioactivity of the comment.

I've come to enjoy the gym, though as with everything in life, I get bored easily. So for the first few months I developed a love for the elliptical, supplemented by a weight training regimen. But then began the affair with the treadmill, and my elliptical romance eventually passed into an oblivion I can no longer access. The cross trainer proved a one-night stand, as did the step machine, though the satisfaction of climbing the height of several famous buildings (so the machine told me) compelled me to engage with it a few times. Now I run (usually outside). And do yoga; I think I could never get bored with yoga as it differs with each class even with the same instructor. Occasionally the rowing machine finds way into my repertoire. But I fear doing much except for yoga with any regularity or frequency because, after a time, they fall victim to my incessant need for change and stimulation.

People-watching at the gym never gets boring, thankfully, for in their exercise people are spectacles. Yet one group or "type" stands out: all of the peacocks strutting about. They seem to glide across the floor of the gym, targeting their next station: chests puffed up, shift sleeves completely removed and the sides slit so deeply one is treated to generous views of sculpted pecs and six pack abs, and, like a parody of John Wayne Westerns, arms bowed as if gun holsters protruded from their hips. These are the young men gripped with Adonis Complexes.

There are many gods in Greek mythology, but Adonis, the god of beauty and desire, possesses a special designation: for his name, from the Semitic adon (from which the Hebrew אֲדֹנָי, Adonai, derives) means lord. Talk about elevation. Adonis: god of gods? Well, yes. Kind of. No wonder we name a complex after him. One wonders if Greek mythology was really Epicurean, or even Bacchanalian, at its core.

By now, dear reader must be thinking: what does this have to do with gardening?

Well, according to legend, when the beloved and dashingly beautiful Adonis died (killed by a wild boar, sent either by the jealous Artemis, or by the spiteful Ares, or by the vengeful Apollo), Aphrodite sprinkled his blood with nectar and thus sprang the anemone, Greek for "daughter of the wind," the short-lived flowers whose petals are easily felled by the wind.

My little Adonis, Gramsci-cat, sprinkled my anemones with a bit of his urine. Believe me: more than the petals fell.

The gardening connection does not stop there. Oh no. I was reading a bit of Erasmus (because we all know that's what we do when we procrastinate) and learned that, in honor of the fallen Adonis, women would sow the seeds of fast-germinating plants in pots each spring.

After the eight day festival of Adonia honoring Adonis' life, beauty, and death, (well, really more his beauty), women would heave these pots from their rooftops into the rivers and oceans to honor the fallen god.

Some have commented that these pots containing shallow rooted plants withered daily in the sun. Hence they were worthless. Theocritus called them "frail gardens, in bright silver baskets kept." Hence developed a proverb--"more sterile than the gardens of Adonis"--presumably to reflect the merely pleasurable, non-productive Adonis Gardens.(Hence I think they should be potted with herbs, which prefer drier conditions.)

I have never been a fan of gardening in pots, precisely because they require daily doses of water--and more during the dog days of summer.

I did, though, have success with Hymenocalis festalis Zwanenburg (Peruvian Spider Lily, though it bloomed several weeks early (and was done blooming by the time of the garden contest in mid-June. And the rosemary and chives, the ferns, and my Japanese maple seem to enjoy dominating their individual pots.

As homage to Adonis and salute to all of those complexes strutting about the gym, my Peacock Orchids (Gladiolus acidanthera) have begun to bloom. Staring into those perfect flowers, I realize how much I enjoy that parade of beauty.

But heaving them from the rooftops? Nary a chance. Inviting them into my home? Well, then, in the interests of semi-full-disclosure, what happens at 410 stays....

The truth of the matter (in the interests of semi-full disclosure) is that I was once, many, many years ago, a self-professed "shadow-itarian:" if it cast a shadow, I wouldn't eat it. I did quickly see the folly of that, and so ate puffed rice, but that was all I ate. I damned myself in many ways. Enough said. My weight issues were an illness...hence the radioactivity of the comment.

I've come to enjoy the gym, though as with everything in life, I get bored easily. So for the first few months I developed a love for the elliptical, supplemented by a weight training regimen. But then began the affair with the treadmill, and my elliptical romance eventually passed into an oblivion I can no longer access. The cross trainer proved a one-night stand, as did the step machine, though the satisfaction of climbing the height of several famous buildings (so the machine told me) compelled me to engage with it a few times. Now I run (usually outside). And do yoga; I think I could never get bored with yoga as it differs with each class even with the same instructor. Occasionally the rowing machine finds way into my repertoire. But I fear doing much except for yoga with any regularity or frequency because, after a time, they fall victim to my incessant need for change and stimulation.

People-watching at the gym never gets boring, thankfully, for in their exercise people are spectacles. Yet one group or "type" stands out: all of the peacocks strutting about. They seem to glide across the floor of the gym, targeting their next station: chests puffed up, shift sleeves completely removed and the sides slit so deeply one is treated to generous views of sculpted pecs and six pack abs, and, like a parody of John Wayne Westerns, arms bowed as if gun holsters protruded from their hips. These are the young men gripped with Adonis Complexes.

There are many gods in Greek mythology, but Adonis, the god of beauty and desire, possesses a special designation: for his name, from the Semitic adon (from which the Hebrew אֲדֹנָי, Adonai, derives) means lord. Talk about elevation. Adonis: god of gods? Well, yes. Kind of. No wonder we name a complex after him. One wonders if Greek mythology was really Epicurean, or even Bacchanalian, at its core.

By now, dear reader must be thinking: what does this have to do with gardening?

Well, according to legend, when the beloved and dashingly beautiful Adonis died (killed by a wild boar, sent either by the jealous Artemis, or by the spiteful Ares, or by the vengeful Apollo), Aphrodite sprinkled his blood with nectar and thus sprang the anemone, Greek for "daughter of the wind," the short-lived flowers whose petals are easily felled by the wind.

My little Adonis, Gramsci-cat, sprinkled my anemones with a bit of his urine. Believe me: more than the petals fell.

The gardening connection does not stop there. Oh no. I was reading a bit of Erasmus (because we all know that's what we do when we procrastinate) and learned that, in honor of the fallen Adonis, women would sow the seeds of fast-germinating plants in pots each spring.

After the eight day festival of Adonia honoring Adonis' life, beauty, and death, (well, really more his beauty), women would heave these pots from their rooftops into the rivers and oceans to honor the fallen god.

Some have commented that these pots containing shallow rooted plants withered daily in the sun. Hence they were worthless. Theocritus called them "frail gardens, in bright silver baskets kept." Hence developed a proverb--"more sterile than the gardens of Adonis"--presumably to reflect the merely pleasurable, non-productive Adonis Gardens.(Hence I think they should be potted with herbs, which prefer drier conditions.)

I have never been a fan of gardening in pots, precisely because they require daily doses of water--and more during the dog days of summer.

I did, though, have success with Hymenocalis festalis Zwanenburg (Peruvian Spider Lily, though it bloomed several weeks early (and was done blooming by the time of the garden contest in mid-June. And the rosemary and chives, the ferns, and my Japanese maple seem to enjoy dominating their individual pots.

As homage to Adonis and salute to all of those complexes strutting about the gym, my Peacock Orchids (Gladiolus acidanthera) have begun to bloom. Staring into those perfect flowers, I realize how much I enjoy that parade of beauty.

But heaving them from the rooftops? Nary a chance. Inviting them into my home? Well, then, in the interests of semi-full-disclosure, what happens at 410 stays....

Tuesday, July 10, 2012

Summer of my (Gardening) Discontent

"Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this sun of York..."

Made glorious summer by this sun of York..."

--Richard III, Shakespeare

Drought. Persistent record-breaking heat. High humidity. Mosquitoes--swarms of them. Sclerotium rolfsii. Sharon.

Drought. Persistent record-breaking heat. High humidity. Mosquitoes--swarms of them. Sclerotium rolfsii. Sharon. These are the causes of the summer of my gardening discontent.

The drought has claimed several plants, most notably several of the Japanese Painted Ferns. I pulled a scraggly chrysanthemum from the raised bed around the maple tree that had finally donned the crispness and color of botanical death.

The Japanese Beech Ferns have lost three-quarters of their mass. Buddha meditates on the impermanence of life (yet I cannot help but think Buddha silently impugns, "impermanence assisted as it were by neglectful people like MSW").

Add to those Gramsci's assistance with watering and fertilizing, well, then, we have a perfect storm. This poor hosta has not had a break; Gramsci prefers to deposit his droppings, and scrape the mulch and soil around it, never caring that each week he breaks another leaf from the crown.

More damningly and disturbingly, he has come to prefer the lavatorial privacy afforded by the Nikko Blue Hydrangea, which, since the gardening contest last month, has been succumbing to the slow creep of death.

One of the Golden Tiara hostas, afflicted last year by Sclerotium rolfsii, has this year been nearly obliterated by it, its flower stalks a tragic testament to resilience.

To add to my woes, or perception of my woes, Sharon asked for lavender yesterday. Her homeopathic therapist suggested she inhale its aromatic oil to help her sleep, which she has not been able to do in any meaningful sense since she returned from hospital four weeks ago. Her body and her psyche exude the failings caused by chronic insomnia. I raced to the garden to face my own denial: the lavender--the massive one that I transplanted earlier this year--was definitely dead. Dessicated. Brittle. Cast in sickly hues.

Gardening has become, like much in life of late, a chore, something to be avoided.

But a walk this morning reminded me of Shakespeare and the power of suggestion and image and perception: "Now is the winter of our discontent, made glorious summer by this sun of York."

Hardly a commentary of Yorkshire weather.

His story demanded an antagonist, a villain. Richard III proved an available figure: an unhappy man in a world which hated him, brooding and melancholic, malevolent even. The portrait continues a few lines down, which is framed as Richard's decidedly non-fraternal feelings towards his brother, King Edward IV:

"I am determined to prove a villain

And hate the idle pleasures of these days.

Plots have I laid, inductions dangerous,

By drunken prophecies, libels and dreams,

To set my brother Clarence and the king

In deadly hate the one against the other:

And if King Edward be as true and just

As I am subtle, false and treacherous,

This day should Clarence closely be mew'd up,

About a prophecy, which says that 'G'

Of Edward's heirs the murderer shall be."

Yet on many accounts Richard III was loved, enlightened, 'forward-thinking'. He proved a loyal and skilled military commander--well, that is until his defeat (er, death) at the Battle of Bosworth Field, the penultimate duel in the Wars of the Roses.

Some Shakespeare scholars opine that the portrait of the dead king reflected his own views of the state of England during the wars when Englishman butchered Englishman, when the House of Lancaster battled, and eventually prevailed over, the House of York and ended the Plantagenet dynasty, the 15 kings of which ruled England from 1154 to 1485. But their paternal ancestors were French, and we all know about the historical (and not so historical) tensions between the English and the French. To Yorkshire pudding Lancaster said yes. To French-descendent kings, a resounding no.

Shakespeare needed a foil--something, someone, to exemplify the fetid gash that divided England, of the plots and schemes and pettiness that fed a war--to prove the futility of (internecine) conflict. We humans thrive, it seems, on nastiness, and therefore nastiness demands a rejoinder.

And so my irenic reading of Shakespeare found an analogue in my garden this morning, an antidote to the summer of my gardening discontent: in my Rudbeckia I found the sun of York, a blazing presence in a drought- and cancer-scarred landscape.

As I drove home from an exhaustingly invigorating yoga class last evening, I thought that I would not have the strength to battle the aggressive cancer that Sharon, nearly 2 years my senior, faces. I could feel her palpable, quite evident exhaustion and frustration, and would want, if I were in her shoes, to simply curl up and die. But she does not budge; her feet remain planted on terra firma all the while she scans the heavens looking for signs from her maker.

Hope remains even in the face of the most adversarial nastiness and discontent.

That we must remember.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)